You might be amazed to learn that Oakland’s Cox Academy improved children’s reading proficiency by reducing the number of tutors at their school. This stunning shift not only improved student results but also cut down on prep time for teachers and tutors and led to better retention of both. When I first heard about this solution, I had questions, but the results speak for themselves. This story illustrates how trust, combined with strong school leadership and innovative thinking, can significantly benefit students. I hope you find it as inspiring as we do.

We sat down with Omar Currie, now in his fifth year as principal, and Kavitha Senthil, a long-time first grade teacher at Cox Academy turned early literacy dean of instruction, to learn more. Following are excerpts from our conversation, which lift up the challenge, opportunities and lessons learned.

What challenges did you face before shifting to the new tutoring model?

Kavitha: When I stepped into my current role I had a year of difficult classroom observations. Students were expected to work independently while the teacher and tutor focused on small group instruction. Students didn’t have the skills to work independently, so teachers had them coloring. Teachers and tutors were struggling to prepare all their small group lessons and independent activities.

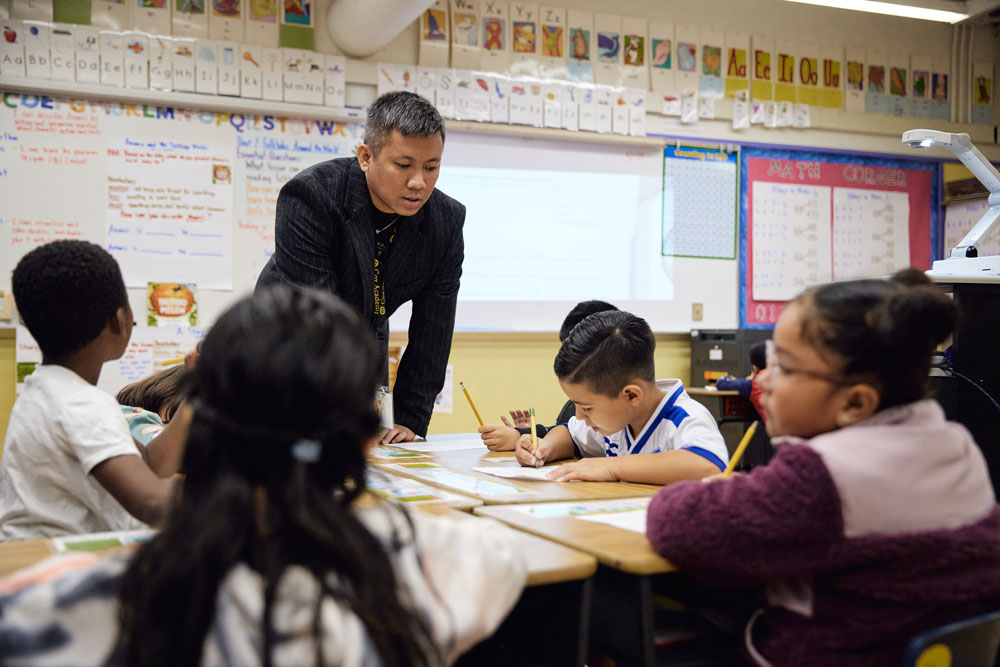

Omar: On paper, our old model should’ve worked, but being in classrooms and observing, it wasn’t working. Students had too much idle time. I at first thought our teachers had low expectations for our students. But I learned that it was a consequence of the model. Teachers had to have kids doing something independent and a coloring sheet is easy.

Tell us about your new tutoring model.

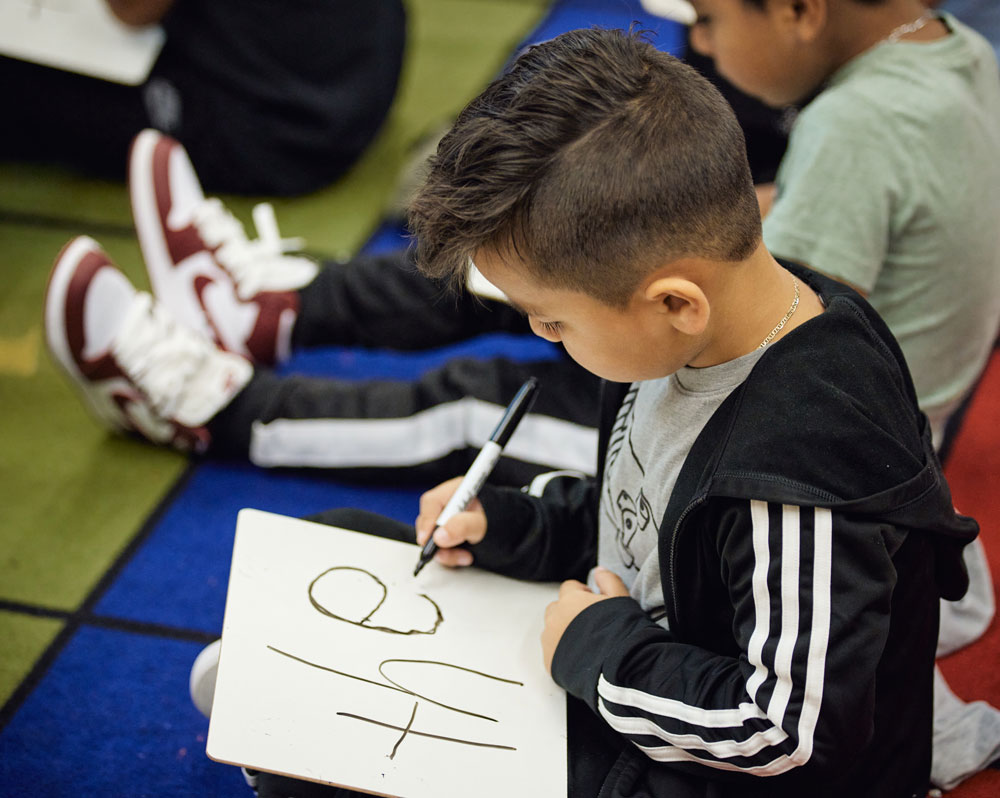

Kavitha: I attended the annual Plain Talk About Literacy and Learning conference, and heard that 80% of instruction should be Tier 1 [evidence-based universal instruction], and Tier 2 [targeted small group interventions] should be reserved for students that need it. I realized at Cox we were doing 100% for both Tier 1 and Tier 2, which meant we didn’t have time for vocabulary and oral language, comprehension and reading fluency. Eighty minutes of our day was focused on a teacher and tutor leading small-group instruction, but two groups of students weren’t learning for 50-80% of that time because they were waiting for their turn with a teacher or tutor and doing a simple independent activity like coloring. All that learning time was wasted every day, which exacerbated the need for Tier 2 interventions.

My plan was to have three tutors and the teacher teaching in a classroom at the same time, so that students were always engaged. This new plan cut the time required for small group instruction from 80 minutes to 30, maximizing learning time and creating time for monitored independent practice and other instruction. When Omar agreed to it, that gave me a boost.

Omar: The solution made sure that students were meaningfully engaged at all times by utilizing the tutors differently.

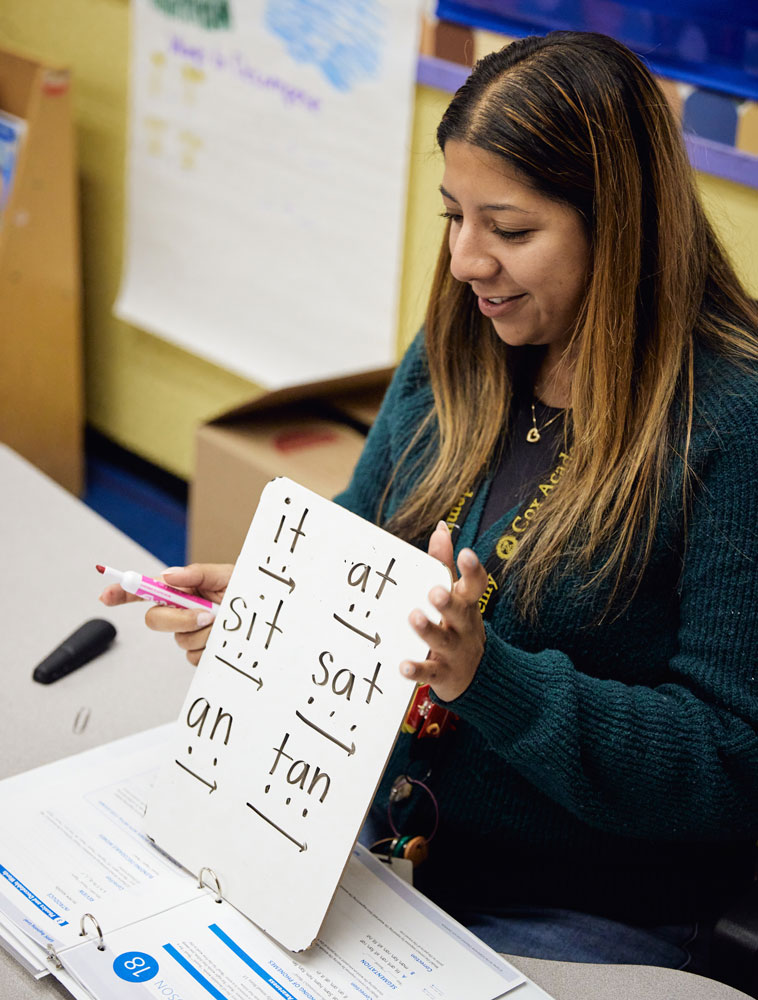

Kavitha: I brought it to the teachers, who weren’t comfortable with it at first. Instead of rotating through multiple groups with one tutor this new plan meant they would see just one group of students during small group instruction, and three tutors would support the others at the same time.

Despite hesitation, about 50% of teachers were willing to try, and the tutors were totally on board. That gave me hope. I worked on the schedule, which showed we could do it. Once we launched, the teachers realized they no longer had to prep multiple small groups or independent activities. It eliminated elements that were blocking learning and causing teachers to struggle. Then we started to see our data improving.

What success are you seeing?

Kavitha: From a data standpoint, 72% of first grade and 73% of second grade students were proficient at the end of the school year on FastBridge assessments. We never had such high numbers. In the second grade, students usually finish their level of the intervention program (SIPPS) in May—or they don’t—but last year, half of the groups met the expected end-of-year level by spring 2024, a first at Cox. That gave us time to provide more intensive work for the other students. The groups that met their grade level expectations early were independent, reading chapter books and doing comprehension work on their own. And this happened in all second grade classrooms.

Omar: The level of rigor in classrooms shot up as did the joy on students’ faces because they felt successful. You can be really proud when you’re given a writing task and you’ve written a whole full paragraph on your own; that’s something that feels good. Seeing our kids be more excited in the productive struggle and see that carry through into other parts of their day has been exciting.

We have a partnership with Families in Action’s Literacy Institute, and it’s been great to hear how excited kids have been to share their reading at home and that it doesn’t feel as taxing as before. Families’ level of investment in what we’re doing and what’s expected in the classroom changed. We’ve made sure our families understood their students’ data. We changed how we did conferences so that families came earlier to review beginning-of-the-year data, and we also brought them in to see our new tutor model. There’s also been a different level of accountability from them to us, which has been impactful.

What additional factors contributed to your success?

Omar: The Rainin Foundation grant helped us hire part-time tutors, and then during the pandemic, we made adjustments to fund them full-time. This shift encouraged a different level of respect for their work among school staff, and inspired a different level of ownership among the tutors. With full-time status, they’re able to say, “This is my community. This school is investing in me and I can invest back in them.” And the work Kavitha needed to do with the tutors—meaningfully engaging them and planning for the future—you can’t do on a part-time schedule.

Kavitha: Our tutors had years of experience at our site and with the curriculum, so we didn’t have to invest in training them. Each day, they teach nine groups, and because it’s the same level for each grade, they only have to prep for three lessons instead of nine. This made it easier to get buy-in, as it reduced their workload. When the teachers saw it was easy for the tutors and saw the student’s results, they were happy to participate.

Omar: Creating a space for people to disagree and speak authentically about their challenges helped. We do a lot of work to support people in feeling like they don’t have to sugarcoat feedback, which makes it easier to problem-solve the actual issue. We acknowledged the difficulties, but cheering people on and painting a picture of success was huge. Clarifying what success would look like on day two versus day 180 was important.

Kavitha: We also brought in a strong Tier 1 phonics program, and students were reading and writing! That was a real struggle before, so when teachers saw the results, they wanted the shift.

Omar: What also fascinates me is that I don’t think we could be where we are without having experienced the pandemic. While really hard, it allowed for a reset and reflection on what we needed to do to address student learning loss. It taught me as a leader how to chart a pathway forward. We didn’t use the pandemic as an excuse, we spent more time thinking about how to make progress. That orientation made it easier for people to buy into the shift because we had built trust with how we handled the pandemic.

Download The Case Study

Learning from grantees is paramount to effective grantmaking, and sharing these learnings is essential to improving outcomes for Oakland children. Explore our case study “How An Oakland School Achieved Record-High Student Proficiency,” which elevates key lessons and takeaways from Cox Academy and the Kenneth Rainin Foundation. We hope this story will inspire other schools that are working to enhance literacy, optimize learning time and improve teacher capacity and retention.

What other challenges did you face?

Omar: Oftentimes, school systems try to replicate things from successful schools to help struggling schools, without having conversations with the folks who are in the specific building. To get buy-in from district-level leadership, we had to make concessions and promises, like that we’d only try it for six weeks, and if we didn’t see results, we’d go back to our old model. There wasn’t trust that we knew what was best for our kids. A lot of times, when our students aren’t successful, it’s because of systemic, instructional issues. Our students weren’t succeeding because of a structural issue with our schedule and the way we were utilizing tutors, not because of a lack of effort that people were putting in.

Kavitha: I remember those meetings. We really had to fight for bringing this model in! Now, everyone wants to come and observe us. One other school is adopting our model this year.

Omar: People have shifted, and that’s a great thing.

What lessons would you share to help others replicate your success?

Omar: Our model works for Cox, and elements of it will work for other schools, but it can’t just be a program in a box. When we’ve looked at other schools’ models, we’ve always tried to look for the ways we’re similar versus different. Leveraging the similarities is more helpful than identifying the reasons why it’s not going to work at your school. How can you take these lessons and adapt the model to your school situation?

Kavitha: Scheduling is a big factor. I need three tutors to get into all nine classrooms in the school day, and they need to have breaks in between. Because we have three classrooms per grade level, it works out well. We also created a solution for students that might be struggling after small group instructions to receive extra intervention support on our minimum days.

Omar: I don’t know that you could do this model without a literacy coach whose only job is to focus on foundational literacy or foundational skills, especially in the first year. There are just too many moving parts, and people need a lot of coaching to be successful. There has to be intentional relationship work between the coach, the principal, teachers and the tutors. There also has to be a baseline level of trust and a willing spirit.

When I first came to Cox, I remember I couldn’t figure out why the school wasn’t doing better. All the pieces for us to be great were here. I realized that people felt like they had never been asked to do better, and that they had never been trusted to make the right choice, so a lot of the work was helping people trust themselves again. That trust was important and it’s important if you were to try to replicate this.

Kavitha: And without Omar saying yes to the idea, I would not have been able to even try it.