Future IDs at Alcatraz was a socially engaged art project about justice reform and second chances after incarceration. Artist Gregory Sale, together with core project collaborators Dr. Luis Garcia, Kirn Kim, Sabrina Reid, Jessica Tully, and many others created this yearlong project in partnership with the National Park Service and Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy. It featured an exhibition of ID-inspired artworks made by individuals with conviction histories and acted as a container for a series of community programs.

With this visionary art project now completed, we invited the collaborators to share their reflections. After watching the above video, three members of the Future IDs creative team—Gregory Sale, Dominique Bell and Kelly Savage-Rodriguez—talked via Zoom with Shannon Jackson (scholar/campus administrator) and Roberto Bedoya (arts administrator/thought leader). During their conversation, they considered how Future IDs at Alcatraz centered the reentry community and held civic space for open dialogue and stories of trauma, transformation, and resilience. The text of their conversation appears below and was edited for clarity.

An Open Conversation

Creating Civic Space On Alcatraz For System-Involved Individuals and Communities

Gregory Sale: The Future IDs project functioned as an invitation to system-impacted communities to come in and co-design programs with us. We invited this big ecosystem of individuals and groups doing work around incarceration, justice reform, and abolition. We said, “Hey, we have this charged site with a specific message around shifting the narrative of reentry. Would you like to use it? Can it somehow expand the work you’re doing?”

We negotiated up-front with the National Park Service (NPS) and Golden Gate Parks Conservancy to provide 200 to 500 free community access tickets per month, to cover the $39 ferry ticket for groups to bring their constituencies to Alcatraz for our co-created programs.

NPS agreed to let us close the doors to make an event private to a specific group, like Sisters at the Center—a circle gathering for women, girls, trans and female-identified folx who have been to prison or jail. Organizers from Los Angeles, San Diego, and the Bay Area came together to design a full day of programs. For much of that gathering, the doors were closed to the public. It would have disturbed a kind of equilibrium for an international tourist or a family to just wander in during a sensitive discussion.

Future IDs created this communal space for dialogue and mutual learning. And it was often an uncertain space where trust was essential. Sharing that space with the public or media would have been premature. I felt that a lot of our good work happened during these closed sessions, off-stage and in the shadows.

The way NPS and Parks Conservancy structure the visitor experience on Alcatraz is in transition. They are asking: if national parks are for everybody, open to all citizens and all groups, how can they expand beyond the primary $39 per visitor model that risks sensationalizing criminals? How can the site serve as a valuable civic forum for local communities to consider incarceration, justice, and our common humanity?

With our programs, Future IDs offered to be a facilitator, the middle person to negotiate between the kinds of parameters within which NPS and Parks Conservancy need to operate and the desires of community groups. As a federal agency, NPS can’t host direct political advocacy, but they can host first-person storytelling. Who are those storytellers? The obvious storyteller is someone who was once incarcerated on Alcatraz. Because the prison closed in 1963, only a few are still around.

NPS and Parks Conservancy has done some good work focusing on other aspects of Alcatraz’s history, specifically the Native American occupation and the birth of the Red Power Movement.

In many ways what we were doing was piloting for the NPS and Parks Conservancy a range of strategies for sharing control over the use of the site with system-impacted individuals and communities. How could we help them come up with new models of continuing this work after we leave?

Producing Systemic Space

Shannon Jackson: Well, Gregory, the complexity of what you just described is something I don’t fully hear in the phrase “holding civic space,” which sounds sort of gentle, and not reflective of the intersectionality and the cross-sector work.

When I hear “holding civic space,” perhaps it’s my mistake, but I hear it almost as if you’re holding onto civic space—as if it’s permanent. I really felt that Future IDs was creating some kind of deliberative, ephemeral civic space that was not there—that it wasn’t a thing that you could hold on to. It was really about imagining a different form. It felt almost like producing systemic space.

Because, as you say, you gathered this ecosystem. You called it. So it’s the fact that you’re gathering all of these people from different sectors: activists, educators, social workers or lawyers, current prisoners, people who have been incarcerated, family members, sometimes survivors of violence, all of whom have different positionality and different skill sets and different reality principles. Figuring out a way to have them in some kind of interaction is like systemic work.

That space was physically on Alcatraz, but also had all of those connections to different/other institutions, whether they be courts or community centers or community colleges, all of that wider network-producing systemic space. You gave NPS and Parks Conservancy this idea of how they could reimagine their systemic position through this project.

It’s so interesting when you talk about the different levels of publicity, shadow, openness, and closeness. Our notion of holding civic space might default to a deliberative governing body. But holding civic space might center on something that happens on the sly over here, secretly over there in a hug, over here in a six-person group, there in a 100-person group, and that was part of the medium that you were manipulating too. I want to get to the naming of the complexity of what you’re describing.

Jumping into Each Other’s Worlds

Dominique Bell: It seems like there are philosophical differences that we have to try and identify: form versus function. What are we calling something? What expectations are invoked by those words? Because when you say civic space, there are so many things that are conjured up.

One thing I loved about Future IDs is that it was the first of its kind on Alcatraz. There is less expectation when something is in its preliminary stages.

There is comfort in not being confronted with a civic space defined by crimes. The public did not necessarily know that Future IDswas about individuals who may have killed, who may have raped, and all that. Many of the participants/offenders created their artwork for the exhibition after they completed their sentences. So, it really was about second chances.

Because I can tell you this, if you say, “There’s a civic forum in downtown Los Angeles for Black Lives Matter,” that gives people information that shapes whether they are going to show up. But if you say, “Today, there is an event about civic engagement and how to better relations among various classes of people,” the ambiguity allows for there to be a congregation of people who otherwise may not have chosen to be there.

There’s an importance to naming something in a way so as not to pollute it too much, to keep it ambiguous enough. When the visitors or participants get there, they then take in the actual content as opposed to having a preconceived notion, which may prevent them from ever getting involved in the first place.

Art is a medium or methodology to get a conversation started. You just want an opportunity for people to start to think and open their imaginations first. You don’t over-tell us what we should expect. You present the work. And then you allow the visitor to say, “Hey, what is this? What is Lopez or Bell trying to say?” Then the reflection and discussion begin, and we jump into each other’s worlds.

Gregory Sale: I appreciated how the exhibition was bright and hopeful and stayed in a kind of ambiguous space. We had to meet the regular Alcatraz tourists where they were. Alcatraz often had up to 5,000 visitors a day. That brightness and hopefulness sort of gave us some cover to do the deeper more uncertain work that we wanted to do. To build on what Dom said, had we named it upfront, we probably wouldn’t have been allowed to do some of it.

At times, we got out on some sort of shaky, uncertain ground based on whatever the collective gathered that day was exploring and how uncertain government is at this time. Some of that work ended up being really profound and transformative.

Encountering The Unexpected

Kelly Savage-Rodriguez: There was no way anyone could have expected some of the things that happened.

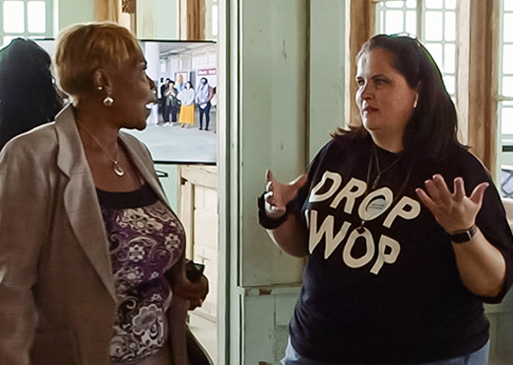

Even with visitors who were just walking into the space, we started having conversations with them to get them talking. They saw people incarcerated as an object in the distance, not everyday people standing around them.

And so that was kind of the fun part because the visitors would be like, “Yeah, but you know their lives are never going to be the same.” I heard that so many times.

I was like, “No, my life is better.” One of the ladies stepped back a little bit when I said, “I just got out after 23 years.” She looked at me and was like, “Oh? Wait. What?” based on how I physically look, which is normal. Visitors don’t expect that, and they didn’t expect that so many people in the room were actually returning citizens.

One of the visitors was just dumbstruck. They had so many questions and wanted so much information that we ended up sitting down. Their questions were really interesting. They had come to visit from England and another one was from Australia. They both impacted me saying this isn’t the way it should be. It shouldn’t be so focused on punishment. It was interesting to me as well to have that opportunity to engage with them, and also give them that clear overview of our system based on my lived experience.

“Is everyone here, here on a serious violent crime?” It was difficult to navigate questions like that. But at the same time, it got them invested in what our justice system looks like long-term. They had expected to find that whole sensationalized story of what Alcatraz used to be. Not an education about the system today and who these people are: those represented by the ID self-portraits and real humans in the room like me.

One gentleman asked me to show him each of the artworks by women in the exhibition. In my one-on-one conversation with him and others, the fact that so many women are incarcerated in the US was completely unexpected. He said, “In my country, we don’t do that.” And that’s how he left it.

Safe, Engaged Space

Roberto Bedoya: Kelly, when you were speaking earlier my mind started to shift a little bit about some of the power of the exhibition. It was both a safe space and an engaged space.

So often in community meetings, it starts off with us saying, “This is going to be a safe space and you can be…” That’s really important, but having the skills and the capacity to create deliberative democracy to have an engaged space is another kind of formality that some people are good at and some aren’t.

And it seems, Kelly, that you know how to do both, to create safe space to allow the individual to come into the circle and feel engaged, even if they don’t say anything. The exhibition also managed to be both a safe space and an engaging space.

We can get lost in trying to understand how porous civic space and public space are. I am in deep reflection right now about COVID-19, a moment of civic trauma when the government is collapsing, when support systems are collapsing, and I hear from artists so often a narrative that is rooted in their personal trauma, whether it’s police brutality or something else. I want it to go further into the systemic space. It doesn’t necessarily go there yet, but I think it will.

We have yet to do the arm-wrestling with the powerbrokers who make pathways for how reentry looks. I know if you’re going to do system change, you have to look at the structures that have created otherness, created prisoners, and created victims. I reflect on the fact that my cousin was in prison for five years up in Pelican Bay and how hard that was. The prison industrial-complex speaks more about whiteness than anything else. That somehow this narrative of whiteness says that, “We put you in jail because you’re a brown man that drinks too much.” Okay, that is my cousin, but he’s not an evil man.

In many ways I want to celebrate the emancipatory spirit of it all. I appreciated the title Future IDs because in a way, you’re prompting the future just by setting up space for the public to imagine the future for somebody whose experience they don’t share and, more broadly, for all of us.

And I love the artist as deliberative practitioner. I refer to the artist as cultural strategist, artist as changemaker, with the skill sets to figure out how to facilitate deliberation, dialogue, and resolutions. That grows in the body of artists like you, Gregory.

When you start saying, “What does that mean—deliberative practitioner?” it means to flow from safe space to engaged space. It means to create exhibitions that prompt dialogue and reflection. In the spirit of “we’re in this dialogue together,” nobody has a magic bullet. We are always kind of unfolding and making and, in that sense, that’s the beautiful art of composing.