The Kenneth Rainin Foundation is pleased to announce that Scott Snapper, MD, PhD, is the new Co-Chair of our Scientific Advisory Board, joining fellow Co-Chair Bana Jabri, MD, PhD. We thank Dr. Averil Ma for his years of leadership as Chair and Co-Chair and are grateful he will continue as an Advisory Board member.

Our Scientific Advisory Board ensures we have a variety of perspectives and experiences to guide our funding recommendations and strategies toward curing Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD). Dr. Snapper represents our priority of bringing science closer to the patient. As a leading IBD investigator and physician, Dr. Snapper has expertise in basic, translational and clinical research as well as biomedical grantmaking.

At Boston Children’s Hospital, Dr. Snapper is the Chief of the Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, and is the Wolpow Family Chair and Director of the IBD Center. He is also a member of the faculty within the Crohn’s and Colitis Center at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Professor of Medicine and the Egan Family Foundation Professor of Pediatrics in the Field of Transitional Medicine at Harvard Medical School. The Snapper laboratory has combined deep basic research in cells and mice with IBD translational research in patients of all ages. They aim to characterize new genes, cells and pathways that are associated with IBD, with a focus on monogenic etiologies associated with very early onset IBD.

I asked Dr. Snapper about his path to IBD research, his leadership in the field and on our Scientific Advisory Board. Explore highlights from our conversation below.

You are highly regarded for your research into IBD and your focus on patients. What drew you into medicine and wanting to work directly with patients as a gastroenterologist?

Dr. Snapper: My father was a small-town family doctor in upstate New York. I saw very early on the joy my dad had in taking care of people of all ages and I did house calls with him. I went as an undergrad to Tufts in Boston, but I knew nothing about science. I came from a tiny town in the second poorest county in New York State. The public schools were strong but there weren’t many opportunities for science until I went to college.

I was first going to be a neuroscientist. But in medical school, I fell in love with immunology and microbiology. Through my mentors, Barry Bloom and Bill Jacobs, I learned the impact of basic research by developing genetic tools to better study mycobacteria, which causes tuberculosis and leprosy. And then I went to India and saw what clinical leprosy was like.

As a post-doctoral fellow, I joined Fred Alt’s lab—still one of the world’s top molecular immunologists—right after the discovery of a gene for a rare immune deficiency called Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome. I was tasked with making a mouse model, and 100% of the mice got IBD. It was the first example of a mouse model of IBD that had a human correlate. In fact, 10% of patients with this rare immune deficiency get IBD. We started using this mouse model, and others have done similar work subsequently, to study the immunological and microbial determinants that lead to IBD.

For years, I have been interested in studying rare cases of patients who have highly damaging genetic mutations that cause IBD. By studying these rare cases you can learn about the common causes of IBD that we don’t understand. One common immune deficiency associated with IBD we have been studying is patients that lack the receptor for IL-10, a hormone important for calming down the immune system. If you can fully understand why a single mutation leads to IBD, this knowledge can be applied to our understanding of all IBD patients.

Initially, I wondered how to best combine immunology and microbiology in a field where I could affect people’s health as their doctor throughout their lifetime. The answer was gastroenterology with a focus on IBD patients.

You’ve been involved with the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation for decades. You’ve also been on grant review committees for the National Institutes of Health, Rainin Foundation and Helmsley Charitable Trust, and you apply for grants. What lessons have you gleaned from these experiences?

Dr. Snapper: Through these experiences, I’ve learned to focus on identifying exceptional talent anywhere in the world and to be open to new ideas. It’s vital for an organization to be honest and transparent, and work together to identify the best talent. It’s important to go into every grant application as an open slate and leave our biases behind and have scholarly debate among the reviewers. And something that I feel strongly about is identifying a diverse talent pool outside of the standard white male bias. That is incredibly important to me and to the Rainin Foundation.

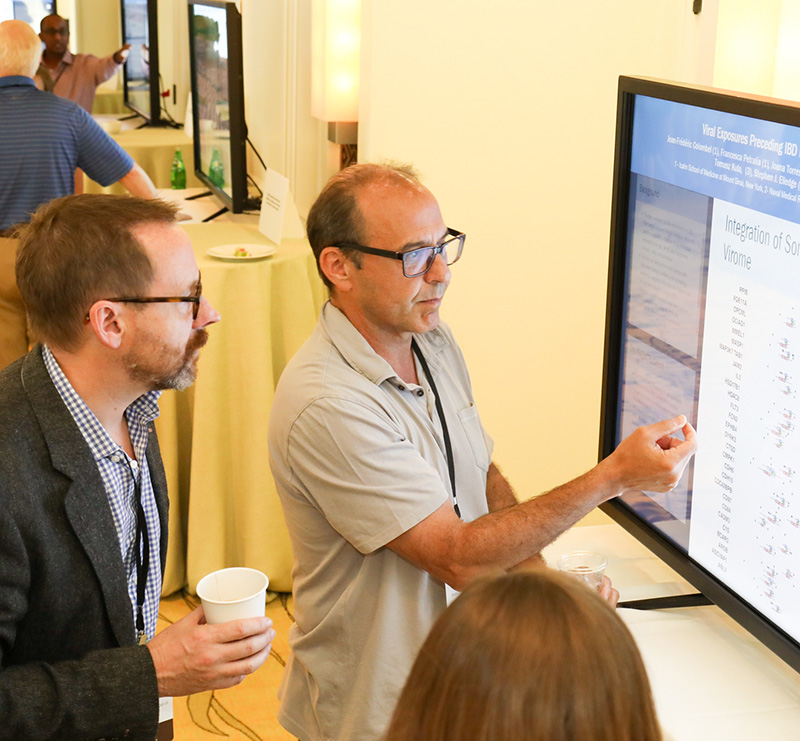

As a grant applicant, I have been fortunate in getting foundation support for early ideas. That’s especially true for a Rainin Foundation Innovator Award in 2016 with Jean-Fred Colombel from Mount Sinai in New York. We came together around a nonstandard collaboration between several institutions and the US military to identify viral exposures that might predict the development of IBD. And we now have exciting data. The Scientific Advisory Board was intimately involved in our grant application and review process, which was atypical in my experience. Without the Rainin Foundation’s support at that first stage, the study wouldn’t have happened.

“Something that I feel strongly about is identifying a diverse talent pool outside of the standard white male bias. That is incredibly important to me and to the Rainin Foundation.”

Dr. Scott Snapper

You’ve been a Scientific Advisory Board member since 2019. What excites you as you move into your new role as Co-Chair?

Dr. Snapper: The Rainin Foundation has promoted transformational inquiry into Inflammatory Bowel Disease for well over a decade. It’s been a privilege to be involved in the innovative program that Averil Ma and Jen Rainin started. Since its inception, the Scientific Advisory Board members have been unbelievably exciting leaders.

The Foundation has put its stake in the ground in fostering people who do not yet have established careers but have shown exceptional promise scientifically. The Foundation is an exemplar of an organization that brings together diverse groups of people and encourages new ideas and approaches. The Innovations Symposium is a unique example. It’s a mid-size meeting that brings together both grantees and prominent speakers, fostering deep interactions and collaborations with everybody.

Everyone on the Foundation’s Scientific Advisory Board is an outstanding scientist with strong opinions. I’ve been exceedingly impressed by their openness to diverse ideas and their ability to leave their egos at the door.

I’m excited to continue working with them, and the research community, to identify the most promising research—basic, translational or clinical—that is going to lead to cures.

“The Foundation has put its stake in the ground in fostering people who do not yet have established careers but have shown exceptional promise scientifically.”

Dr. Scott Snapper

Where will IBD research be in 10 years?

Dr. Snapper: In 10 years we’ll have new therapies and potentially some cures for small populations of patients but we’re not going to be done. We must identify the best talent. That includes identifying young, diverse talent to carry this work beyond the next 10 years. I’m thrilled to be part of that process.

If you had asked me 10 years ago, could the work that we do in the lab affect people’s lives? My answer would have been “Of course, that is why I do what I do, and I hope my work helps.” What I can say now, is that we find things monthly in the lab that affect the patients we see. We are at the point where personalized care for IBD patients—precision medicine—is possible. That, to me, is incredible. Today, saying “cure” is not fantasy.

“We are at the point where personalized care for IBD patients—precision medicine—is possible. That, to me, is incredible. Today, saying “cure” is not fantasy.”

Dr. Scott Snapper