Despite having a job lined up in advance of his family’s relocation back to the Bay Area, Taji Brown couldn’t resist inquiring about a job listing to help launch Early Literacy Kings within Oakland Unified School District (OUSD). “What brought me to this work,” Brown says, “was getting together with young men of color to change our young scholars’ trajectories and experiences. That drew me in.”

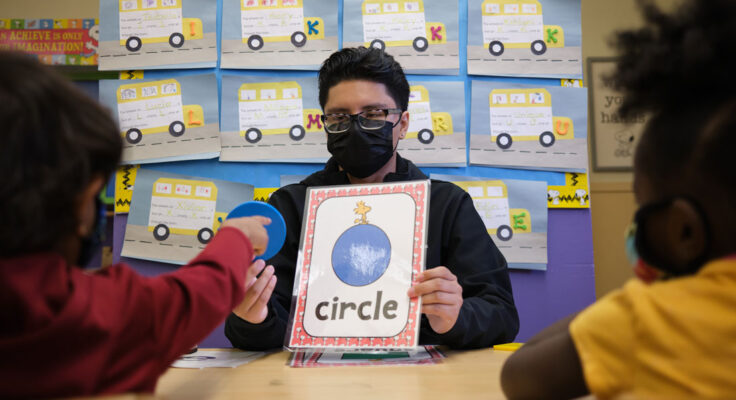

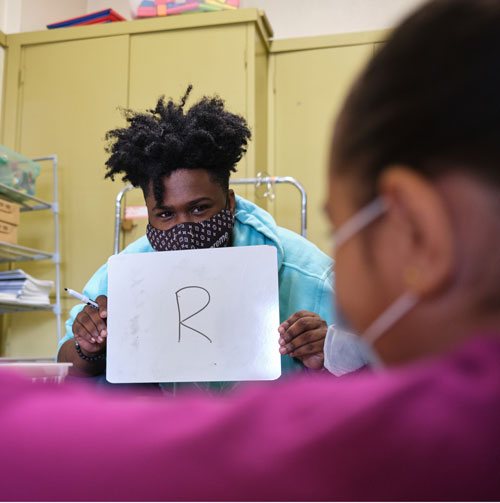

Early Literacy Kings, for which Brown serves as Program Manager, addresses the shortage of men—and especially men of color—in the classroom by creating pathways into education careers. Supported in part by a multi-year grant from the Kenneth Rainin Foundation, the program recruits men of color between the ages of 18 and 24 to be highly skilled classroom tutors. The program has worked with community-based organizations, city government, OUSD, and the District’s Office of Equity for the past two years to recruit graduating seniors into the program. These tutors—or “Kings,” as they’re called—are placed in classrooms where they gain hands-on experience, while also receiving professional development, mentorship, and other supports to help them navigate the system and pursue successful careers in education.

Early Literacy Kings uses SEEDS of Learning, a relationship-based professional development program that provides educators, parents, and caregivers with strategies to build social, emotional, language, and literacy skills in young children. SEEDS of Learning is run and managed by FluentSeeds. The Foundation began funding SEEDS of Learning in Oakland in 2014, and it’s delivered years of promising student outcomes. Recent research conducted in Oakland shows that just one year of SEEDS of Learning has a statistically significant, positive impact on student early reading skills and on teacher knowledge.

Changing Narratives

Brown says that the SEEDS of Learning model and the Early Literacy Kings’ approach serve to change the narrative around who is to be a teacher, challenging the dominant perception that educators are often white women. Shifting the narrative is important for students; a growing body of research confirms that students benefit when teachers share their race or gender. Brown points to the distinct benefit that comes from Kings having shared experiences with and reflecting the identities of the scholars. “We also need to reflect for students that this path is possible for them,” he says. “Having Kings from the same community makes the difference. They can draw from their own experiences to provide successful connections.”

Brown gets a surge of energy when he talks about the power of reflection in the Early Literacy Kings’ model, which provides young scholars with an image of who they could be. “Our young scholars are in for a treat,” he says, emphasizing that having a young man of color in the classroom provides another picture for scholars, but it’s much deeper than that. “Yes, they’re safe,” he goes on. “Yes, they’re secure; yes, there’s somebody in the classroom who understands them.”

The power of Early Literacy Kings in the classroom goes beyond optics. Their impact extends to language, culture, and academic progress, and also reaches outside of the school building to families. Brown shares the example of one of the founding Kings, an English and Spanish speaker, who joined a bilingual classroom in which the lead teacher only spoke English. The first day he showed up, he began to translate for the teacher. Within a week, the class size doubled and attendance skyrocketed. “Because,” Brown says, “he was able to speak the home language of the parents, they were comfortable.”

Differentiated And Adaptive

Since its inception, the Early Literacy Kings’ model has been built on educating the whole child and having a two-way street of mutual respect. So when COVID hit in 2020, just as Early Literacy Kings was getting off the ground, the team was well equipped to work in ways that the moment demanded: intentionally, adaptively, and with clear vision. “It’s really just meeting our scholars where they are, and then building from there,” Brown says, speaking to the responsive nature he and his team embody.

More than anything, Brown says, adapting to pandemic-related restrictions and implications was about putting theory into action. “We had been talking about inequity, but because we hadn’t reached a certain point, we were able to continue life as it was. But COVID brought about a different change; when it shut everything down, it really showed who had access and who did not.” Then it was time to make the walk match the talk, according to Brown. To be intentional and specific about resource allocation, who gains access, and in what order. “No longer did we just see a classroom,” he reflects, “but we had to see each student and family for that family.” Brown’s perspective on educating through COVID illuminates the need for differentiated education—a need that’s always been present, but that’s grown more evident and consequential during the pandemic.

Looking Forward

While Early Literacy Kings is too young to have data to share on its ability to increase the representation of men of color in the classroom, the anecdotal evidence suggests to Brown that many current Kings will take advantage of the program’s supports and pursue careers in education.

Moving forward, Brown and his team are focused on providing financial literacy resources for Kings, leveraging OUSD’s human resources and retention department to position Kings for careers in the district, identifying mental health supports, and recruiting more Kings so that more young scholars can benefit from their powerful presence.

At its core, Early Literacy Kings is a contribution to a brighter, more equitable future. “The program is opening up more doors of opportunity and giving Kings and scholars that exposure. It creates a greater pathway and gives them a further reach.” The impact of the program will grow exponentially, as one King influences a room full of scholars who go on to fulfill their dreams, occupying roles in which they’ll, in turn, inspire rooms full of young people.